Chambered Nautilus hemishell showing the camerae in a logarithmic spiral. Via Wikimedia Commons

You are the temple of God

When I was in high school I memorized The Chambered Nautilus by Oliver Wendell Holmes. I’ve forgotten most of it now, but the first part of final stanza has stayed with me, the part of the poem that I loved best

Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea!

The words of the poem came to me again today, as poetry will, unbidden, as I was meditating on the second reading, from St Paul’s letter to the Corinthians:

Do you not know that you are the temple of God,

and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?

If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person;

for the temple of God, which you are, is holy.

As I was thinking of what St Paul says, “You are a temple of the Holy Spirit,” and of the lines of the poem, “Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,” I was also mindful of St Teresa of Avila’s Interior Castle, in which the saint envisions the soul as a castle composed of seven successive interior courts (aka dwelling places, chambers, or mansions), each successive one being inside the outer courts and closer to God until in the innermost one the soul finds God’s dwelling place. (This also reminds me not a little of Narnia’s rallying cry in The Last Battle, further up, further in! At the center of the country is a garden and that garden contains a whole country and in the center of that country is a garden. . . .)* Anyway, as I was thinking about St Paul and St Teresa and the Interior Castle, it struck me that Holmes’s poem gets the imagery more than a little wrong. The mansion doesn’t shut the soul from heaven, but makes a room for heaven within. As we journey or build, the mansion, or temple, or the soul becomes the throne room for the king, the presence of the kingdom of heaven within. The soul’s task is to make greater and greater rooms, with more and more space for the Holy Spirit to indwell.

Holmes concludes that eventually the soul will be freed from the shell of earthly life, the body outgrown and discarded while the soul is presumably free to seek heaven. This is not exactly a Christian vision, however lofty and inspiring Holmes’s imagery is. The freedom I seek is not only for that day when death will free me to be with Christ, but for now, echoing the prayer of the Lord’s Prayer, “thy kingdom come,” a longing for the Kingdom of God to be established now, here, within. Death is not freedom from an outgrown shell, though, it is the beginning of a new life and we look forward to the day of Resurrection when we will be reunited with our new, glorified bodies, not unneeded shells but integral to who we are. For we are not a body-soul duality, but embodied souls, persons who are both a body and a soul.

*(I wonder, too, do Teresa’s mansions get successively larger as you travel further in, each one a sort of Tardis, bigger on the inside? Now wouldn’t that be cool?)

+ + +

In the Walled Garden

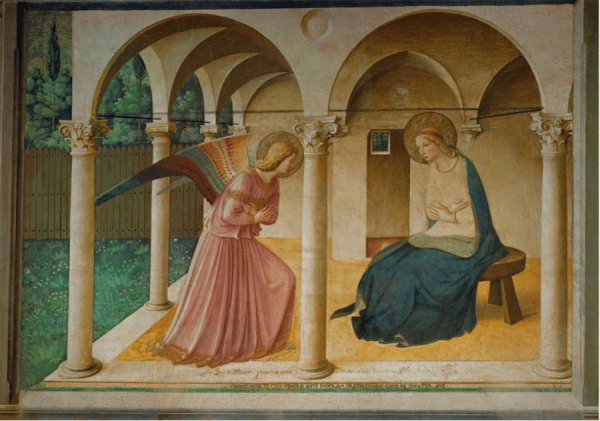

To shift to a slightly different imagery, medieval art often imagines the soul as a cloistered garden. Fra Angelico’s beautiful fresco of the Annunciation shows Mary in a cloister that opens onto a garden. This week I enjoyed reading this beautiful meditation, Theology in Paint by James Patrick Reid, on the meaning and the mystery of the painting as a sermon in shape and color.

I especially enjoyed Reid’s description of the imagery of Mary set off in a space of her own, the Holy of Holies, the Tabernacle:

Note how the second triangle (F) is more vertical than the first (E), halting Gabriel’s advance just before the column that bounds the zone of the painting which represents the Holy of Holies, the space housing Mary, who will henceforth be the Tabernacle of the Most High

We are invited by both St Paul and by Fra Angelico, aka Blessed John (Giovanni) of Fiesole, to imitate the Virgin, to make our own souls a cloistered tabernacle, a walled garden, a place of quiet prayer and contemplation. Although we live in the world, not in the monastery, we can still carry the monastery within. Reid concludes:

Even in city streets and subways, if we guard and cultivate the gardens of our souls through attendance at Mass and private prayer, helped along by frequent contemplation of great sacred art, we find that, day by day, like a friar in the cloister of San Marco, we are led ever deeper into the mystery: God became man so that we might be made divine through union with Him.

+ + +

Private Words Addressed in Public?

Madonna of the Rose Garden Attributed to Michelino da Besozzo (more probably) or to Stefano da Verona (old attribution) – via Wikimedia Commons

But my musings today want to lead me out of the cloister and back into the world, to the weird semi-public, semi- private online spaces of blogs and social media, which Pope Benedict called us to make our mission territory when he exhorted us to evangelize the digital continent. I’m thinking about how to navigate this tricky path of talking about the private in public, the liminal space Eliot refers to in his public love poem to his wife, A Dedication to My Wife: “These are private words addressed to you in public.” How do we talk in public about those private rose gardens “which are ours and ours only,” about the intimate moments when souls are in communion with each other, the “wakingtime” and “sleeping time,” as Eliot calls them? How do we talk about the breathing together and the thoughts that communicate themselves without need of speech and the speech that babbles without need of meaning? Are these too intimate for poetry? Does Eliot trespass by sharing them?

I think there are perhaps cloisters within cloisters, there is private and then there is private. Our souls should be walled gardens and we should be careful not to let them be trampled. And yet there seem to be times to at least describe some of the features of those gardens, to allude to them, to even dare to put into words something of those moments that are the most private and the most intimate. Because to be human is to also build castles of words and to be Christian is to also be a witness, to seek to share Christ, to help others to know Him as we know Him.

Yes, we must be on guard not to be pharisaical about trumpeting to the world all the intimate details of our prayer life —and, as Lent is approaching, our fasting and almsgiving as well— for the sake of receiving praise and admiration for our good works. Yes, we should pray to our Father in secret and, yes, we should take care not to let the left hand know what the right is going.

But does that mean we should never talk with others about our spiritual reading or share fasting tips or ideas for what to give up and what practices to add? Should we never reveal details about graces we have received or share revelations we have received in prayer when the Spirit seems to prompt such sharing? Sometimes there are good reasons to share these things, to develop spiritual friendships, to encourage others who walk the pilgrim path with us. There must surely always be room for love poetry and devotional poetry and spiritual writing and those human ways of performing and sharing what is most intimate with the vulgar crowd without actually letting the vulgar crowd into the secret sanctuaries of the soul.

The question I always ask when I begin to write about such things is: Why am I sharing? Is it because I want admiration or because I want to help a brother or sister, even an unknown one, along the way? Is it out of pride or humility? What is the genre, what is the context, what is the intent? Not all spiritual practices are private devotionals done only within the innermost cloister of our being, some are public gestures, visible to all, and some exist in an in-between place and may or may not be shared depending on individual circumstances, dispositions, and needs.

If the soul is a castle, perhaps we have some chambers which are private, and some which are public, and some to which we may invite only a select company. The soul selects her own society then shuts the door.

We are also called to be a light shining in the darkness, not hidden but placed on a lamp stand, a city on a hill. How can I be little and hidden and yet invite the unknown multitudes into this fine and private space of my blog? How can I dare to write about the private cloistered gardens of the soul in letters big and bold?

The soul creates Mansions in which there are many rooms, private oratories for quiet contemplation and ante-chambers for receiving guests. And maybe even ball rooms and feasting halls, theaters and lecture spaces where crowds may gather and community may be formed. Surely there is room for many kinds of rooms: rooms for sharing and rooms for hiding away?

In addition to a vision of a hidden garden, I have another vision: A door open. An invitation issued. A welcome mat out. Here, come in, let us share a cozy little talk about some of the gardens we have known. Surely there is also room for us to be like Benedict and Scholastica, staying up all night discoursing about God, conferring about spiritual matters, and enjoying the “mutual comfort of heavenly talk.”

Hortus conclusus (walled garden) depicted by Meister des Frankfurter Paradiesgärtleins

via Wikimedia Commons

The post Building Stately Mansions appeared first on The Wine-Dark Sea.